For the last ten days or so, I have been crazy from the heat, sick as a dog, demented by details and generally inattentive. But all the while I’ve been planning to post a piece here, which I finally decided to call Major Minor, which is the name of a fine Peter Blegvad song that appears on his album, The Naked Shakespeare.

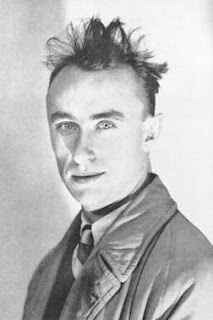

Originally, I had simply intended to write a short appreciation (because I am not a professional critic, that seemed to be the proper appellation for my projected effort) of the 20th century English novelist and playwright Patrick Hamilton, who is probably best known for his successful stage plays Rope and Gaslight, both later made into famous, highly regarded motion pictures. Although I enjoy both plays (and think the recent transformation of “gaslight” into a verb is fascinating, if disturbing, language and behavior issue), I strongly prefer Hamilton’s novels (early to late, from Craven House through Unknown Assailant) and thought I would include in the post the section of Claud Cockburn’s memorable introduction to The Slaves of Solitude where he recalls Hamilton’s extraordinarily acute powers of physical and psychological observation, even in crowded settings like London pubs, which can overwhelm most people with their buzz and din, and his “bat’s wing ear” for dialogue. I also planned to include several selections from Hamilton’s work, including an excerpt from his remarkable, underrated early “graphic novel”, Impromptu In Moribundia (which illustrates Hamilton ability to raise and transform what might be viewed as tiresome political polemic into genuinely moving story-telling and art), and the short final section of Mr. Stimson and Mr. Gorse where we leave the story of Ernest Ralph Gorse (Hamilton describes his protagonist as “the worst man in the world” and creates a riveting portrait, sustained over a long haul, of a sociopath) proper, and are suddenly placed on a different plane of convincing, frightening prophecy, which has unfortunately proved to be a largely accurate picture of European and western life. Rounding the post out would be the inclusion of several charming “author photos”, including the one showing the great man’s drawing room in his flat at The Albany in London (also home to Lord Byron, William Gladstone, Raffles, Jack Worthing, Graham Greene, Anthony Armstrong-Jones, Sir Kenneth Clark, Terrence Rattigan and Terence Stamp, among other notables).

In any event, on my way to “there” (“there” being the composition and publication of the post), I ran into the following quotation about Hamilton from the English critic D.J. Taylor:

“Every so often, though, the revulsion slips away and one is left with the joke or the sideways glance, the twitch upon the psychological thread that guarantees Hamilton a singular place as one of the great minor English novelists.”

The word and classifier “minor”, which I have seen applied untold numbers of times in various ways to artists I admire by critics I don’t, stopped me dead in my tracks. As it usually does, it made me angry for a while and arrested forward motion. I’m feeling better now and would like to say (as briefly as I can manage) that for some reason it appears that many of the artists I admire most are regularly classified as “minor”. Henry Green, who I consider to be the greatest English writer of the 20th century and an incomparable genius, has regularly been called minor. The extraordinary Ronald Firbank, author of Considering The Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli, a writer of peerless wit, facility and humanity (read Sorrow In Sunlight) – minor. Denton Welch, the brave, gimlet-eyed soul who achieved so much as a writer in his short life, ending with the masterpiece A Voice Through A Cloud, is generally considered minor. And Julian Maclaren-Ross, a short story writer, memoirist, critic, parodist and novelist of uncommon character and quality (and the only critic with the sense and integrity to praise Patrick Hamilton’s uniformly loathed conclusion to The Gorse Trilogy, Unknown Assailant) is , for some pitiable and misguided souls, an artist placed at the minor end of minor.

I believe (and recall being taught) that classification was a key intellectual step forward for mankind, through which we bring order to the chaos of our copious, but disheveled, direct observations of life, supposedly in a rational and effective pursuit of our desire to discern “first principles”. That being said, I haven’t encountered (as far as I can discern) the intellect, soul or any other aspect of Aristotle in critics who expel the word “minor” like a puny bullet, damning artists with faint praise in order to elevate themselves to a plane higher than their target. The practice reminds me of a remark I read the other day in a magazine article about the “longshoreman philosopher” Eric Hoffer: "Rudeness is the weak man's imitation of strength”.

Critics apply this “major/minor” idiocy/fallacy to other arts also and I confess to having a consistent record of finding talent, value, genius and pleasure in “minor” figures across the spectrum, from the Greek poet Archilochus to the artists of the French rococo period, from the French painter Yves Tanguy to the American painter of small details, Vija Celmins, from the English expatriate songwriter and pataphysician Kevin Ayers to the American expatriate songwriter and cartoonist Peter Blegvad, both artists of surpassing talent whose “crime” against “major-ness” was simply never having had a big commercial hit.

(Notes to probably already bored readers:

1. I have decided to dispense with the fuller list and to give only the several examples cited above. I could go on and on. N.b. I am leaving The Kinks out of this.

2. I am a Quaker, which is, I suppose a “minor religion” in some people’s eyes, although such a conclusion would be inaccurate in any number of ways.

3. Peter Blegvad is the author of one of the world’s longest grammatically correct palindromes. “Peel’s foe not a set animal laminates a tone of sleep.” MINOR? I ask you.)

In conclusion, I would like to offer my “crazy from the heat” friends (and their parents in the case of Recipe 2 below) something delicious for relief from the high temperatures and stress of it all:

Recipe 1: Papaya-Banana Smoothie

1 cup milk

1/4 cup Greek yogurt

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

1 small ripe banana, peeled and sliced

1/2 large, ripe papaya, peeled, seeded and chopped

1 cup ice cubes

Combine the milk, yogurt, vanilla, banana, papaya and ice cubes in a blender and blend until smooth. Pour into a large glass.

Recipe 2: Mango-Yogurt-White Rum Smoothie

2 ripe mangoes, peeled, pitted and chopped

2 cups Greek yogurt

1/2 cup mango nectar

1/2 cup white rum

Crushed ice

2 to 4 tablespoons simple syrup, depending on sweetness of mangoes

Combine mango, yogurt, nectar, rum and a few cups of crushed ice in a blender and blend until smooth and frothy. Sweeten with simple syrup, if needed. Divide among 4 glasses and serve.

Stay cool. A toute a l'heure.

i wish i had a papaya with me to make the first smoothie.

ReplyDeleteMe too. I have only peaches and limes with me at the moment. Hey, I have an idea......

ReplyDeleteI went to this market place yesterday and they were selling these giant papayas and so I bought one and made the first smoothie and it was reeeaallyyy good :) Thanks for the recipe :)

ReplyDeleteDear Nameless,

ReplyDeleteThat's great to know. I think I'll be buying papayas (about my favorite fruit) later.

By the way, English teachers will eventually hit you with the whole major/minor "idiocy/fallacy". It's a pretty useless way to look at literature (and the world), but it's best to play along while you're still in school and agree with them. However, the important thing is to consider "the thing itself" and always make up your own mind based on the evidence.

Yours,

AC

Up with the minors! Kingsley Amis said,

ReplyDeleteImportance isn't important. Good writing is.