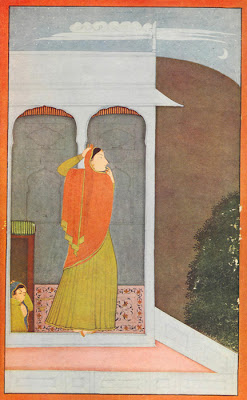

The style of the Rajput paintings is an archaic, unsophisticated style. The figures mostly appear according to the principle of “perfect visibility,” which is contrary to any attempt at giving the illusion of a third dimension: the heads are shown in profile, but with the visible eye in full length, the chest is displayed in full expanse and the gestures are confined to the front plane. The background is, comparatively, simple; buildings as well as landscape settings have often to serve a linear system of surface organization reminiscent, in a fashion, of the compartmental sectioning of the Gujurati miniatures. But the figures with their striking gestures and expressive attitude convey a feeling of tremendous energy and the background is penetrated by their own emotional atmosphere.

Emmy

Wellesz, Akbar’s Religious Thought Reflected

In Mogul Painting, London, George Allen

and Unwin Ltd, 1952.

Upper: THE EXPECTANT HEROINE. Kangra school, early

nineteenth century. Painting on paper. Lady Rothenstein collection.

Lower: VAIKUNTHA, THE HEAVEN OF VISHNU. Rajasthani school, about 1750. Painting on Paper. Lady Rothenstein collection.