Now, if my friend had come to Ischia instead of poisoning himself with fusel oil sold as whisky by honest colonial traders, he might have drunk as much as he pleased and been all the better for it. For wine is the water of Ischia, and as a vino da pasto it is surpassed by none other south of Rome. Indeed, it is drunk all over Europe (under other names) and a pretty sight it is to see the many-shaped craft from foreign ports jostling each other in the little circular harbour, one of the few pleasing mementos of Bourbon misrule. The Austrian, battling with his Paprikahendl, or the Frenchman ogling his omelette and his yard of bread, little dream how much Ischia has contributed to their Gumboldskirchner or vin ordinaire. Try it therefore through every degree of latitude on the island, from the golden torrents of thousand-vatted Forio up to the pale primrose-hued ichor, a drink for gods, that oozes from the dwarfed mountain grapes. Try also the red kinds.

The waters of Ischia

Try them all, over and over again. Such at least was the advice of a Flemish gentleman whom I met in bygone years in Casamicciola. Like most of his countrymen, Mynheer had little chiaroscuro in his composition; he was prone to call a spade a spade; but his ‘rational view of life’, as he preferred to call it, was transfigured and irradiated by a profound love of nature. Where there is no landscape, he used to say, there I drink without pleasure. ‘Landscape refines. Only beasts drink indoors.’ Every morning, he went in search of new farmhouses in which to drink during the afternoon, and late into the evening. Every night, with tremendous din, he was carried to bed. He never apologized for this disturbance; it was his yearly holiday, he explained. He must have possessed an enviable digestion, for he was up with the lark and I used to hear him at his toilette, singing strange ditties of Meuse or Scheldt. Breakfast over, he would sally forth on his daily quest, thirsty and sentimental as ever. One day, I remember, he discovered a farmhouse more seductive than all the rest—‘with a view over Vesuvius and the coastline, a view, I assure you of entrancing loveliness!’ That evening he never came home at all…….

Excerpt from Isle Of Typhoeus (1909) -- Norman Douglas

Zeus hurling his lightning at Typhoeus, Chalcidian black-figured hydra, ca. 550 BC, Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich

Reading Norman Douglas's Isle Of Typhoeus, written when Douglas was already 41, midway between his first book Unprofessional Tales (1901) and his most famous novel South Wind (1917), both calms me down and lifts me up, two things I find I need very much these days.

I learn so much so enjoyably and easily from Douglas that I don't even mind when the gaping holes in my education are revealed in super-high relief (or, as I suppose I should say, high-definition void). I'd like to think there's still time to rectify (or at least ameliorate) the situation and definitely time to steer (I would like to say, "continue to steer") Jane on the right course in her own studies.

"The Frenchman ogling his omelette and his yard of bread". That's really great, I think, and so is all the rest, which immediately takes up permanent residence in memory and reference frame.

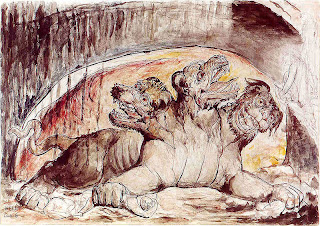

I wasn't sure at first why Ischia was referred to as the Isle Of Typhoeus in Douglas's title, but if you are interested, you can find a great deal of information about the terrible Typhoeus, father both to Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding the gates of Hades, and Chimera, monstrous fire-breathing female creature of Lycia in Asia Minor, composed of the parts of multiple animals (upon the body of a lioness with a tail that ended in a snake's head, the head of a goat arose on her back at the center of her spine): Here.

William Blake, Cerberus. Pen, ink and watercolor over pencil and black chalk, Date unknown (18th century), National Gallery of Victoria, Australia

Regarding Typhoeus's relation to trapezoidal Ischia, largest of the islands in the Bay of Naples and neighbor to Douglas's compass point, Capri, some versions of the complicated and sometimes contradictory Typhoeus stories inter the vanquished monster underneath Mount Etna in Sicily, but others bury his tangled corpse under the sea at Ischia, giving birth to the island.

Eternal fires of Chimera in Lycia, Turkey

As an Ischia tourist website puts it (in slightly awkward, but still servicable, English translation):

"According to a legend, the Isle of Ischia was born out of the body of the giant Typhoeus, son of Tartarus and Gaia, who gave him birth with the intention to transform him into an opponent of Zeus and avenger of Cronus, whom she wanted the throne of the gods to be given back. He looked like a monster with hundreds of snake heads, burning eyes and a voice "now as of a superb bull, with a strong low and an unrestrainable power, now similar to the barking dogs, a marvel to be heard, now whistling and echoing in the big mountains." The giant, faithful to his mother's teachings, rebels to Zeus, who gets very angry and during a fight throws him into the "depths of Tartarus". Homer himself mentioned the myth of Typhoeus in his Iliad (II 780-783), but he set the whole scene in the land of the Arimi: "Thus marched the host like a consuming fire, and the earth groaned beneath them when the lord of thunder is angry and lashes the land about Typhoeus among the Arimi, where the say Typhoeus lies." Thus Typhoeus was thrown down the Olympus and generated the island of Ischia. Today many areas of the island are said to owe their name to the parts of the giants body: Piedmonte (at the feet of the mountain), Testaccio (head), Panza (belly), Cigilo (eyebrow), Molara (molar), etc........."

Ischia

Adding to the relaxed, late afternoon-early evening, change-of-seasons, vino da pasto atmosphere that I hope suffuses this post, you will find below an interesting 1952 (the year Douglas passed away in Capri) photograph of W.H. Auden in Ischia seated between his portrait and portraitist, Bolivar Patalano. Patalano, a well-known Ischian painter, according to his friend and fellow artist, Philip Dawes, "lived for about 20 years in the U.S.A., of which ten were spent in prison for the murder of someone with whom he had a drunken brawl It was in prison that the psychiatrist suggested that he take up painting as a means of calming his emotions and thus he took to painting like a duck to water."

I like the photo; I wonder what Auden thought of the portrait?

No comments:

Post a Comment